Integrating Spokestack with Google App Actions, Part 2

This tutorial is part of a series:

- Part 1: Working with Google App Actions

- Part 2 (You are here!): Adding your own voice experience with Spokestack

- Part 3: Using Spokestack Tray to add a voice UI

In the first part of our tutorial, we talked about how to make an Android app’s features available via Google App Actions. In this part, we’ll take it to the next level and show how to continue the user interaction via voice once Google Assistant has dropped the user off inside the app.

From actions to intents

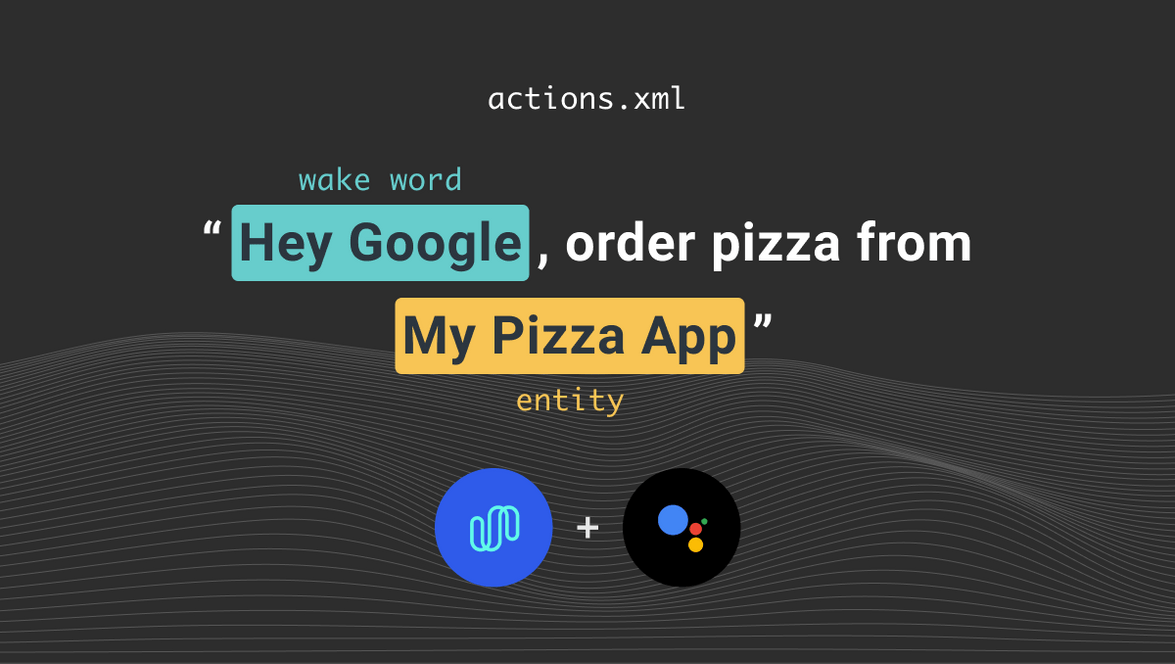

First, we’ll need to recreate the ability to act on natural-language user requests, which is a job for an NLU. Luckily, we’re already halfway to configuring one, thanks to the actions.xml file required by Google. As a quick reminder, it’s in the res/values/xml folder in the sample app.

If you’ve worked with voice platforms before (or read the page linked in the last paragraph), you might notice some familiar concepts in that file, especially if you’ve used any custom intents in your app. intentName is … well, the name of the intent, parameters are slots, and queryPatterns are utterances. If you’re using a built-in intent, like GET_THING in the sample app, queryPatterns is hidden from you, handled entirely by Google, but the other things are still there.

We’re going to exploit that similarity and convert our XML directly into Spokestack’s NLU format, using it to create a custom NLU model that will replicate the features we’ve just defined for Google Assistant in our app itself. This is a great opportunity to add new intents to your in-app NLU that would be too tricky or infeasible to expose via Google Assistant.

We won’t go over the converted versions of all the intents here, but here’s the Spokestack version of the navigate.settings intent from actions.xml:

description = "the user wishes to view the settings screen"

[generators.verb]

type = "list"

values = [

"see",

"show",

"give me",

"open",

"change",

"update",

"go to",

"take me to"

]

[utterances]

values = [

"settings",

"settings screen",

"settings screen please",

"{verb} settings",

"{verb} my settings",

"{verb} the settings",

"{verb} the settings screen",

"i want to see my settings",

"i want to change my settings"

]In Spokestack’s format, you can achieve the same effect as Google’s conditionals (the parenthetical words and question marks in the XML) using generators. We’ve added a few more utterances to the Spokestack config than were present in actions.xml because they’re a little easier to express here.

The description field is optional but can help you think about the interplay among your various intents.

For sake of demonstration, we’ve included all the Spokestack NLU files in src/main/assets/spokestack-nlu. We’ve renamed the GET_THING buit-in intent to command.search for in-app usage and supplied our own utterances for it. You won’t need to actually create a model with these to run the tutorial code, though, because the trained model is in the assets folder as well. We’ll talk about how to use it … right now.

App logic

Integrating Spokestack

Now that we have both App Action and Spokestack NLU configuration in place, let’s look at how to handle voice input with Spokestack once the user’s already in your app.

You probably noticed in the first part of the tutorial that our sample app is a bit of a hodgepodge with no particular purpose other than to cover a few common use cases for voice control. Humor us here. The app has 4 total layouts, one that serves as a main menu and three others that demonstrate different potential features. Each scene has its own activity.

To process voice input, all you need is an instance of Spokestack and a subclass of SpokestackAdapter to receive events. Since we have multiple activities and want them all to be voice-enabled, we’ve made a Spokestack instance available via a singleton (see the Voice object) and created an abstract VoiceActivity to be extended by all activities that need access to it. Each VoiceActivity is responsible for creating its own SpokestackAdapter because each has its own UI that needs to be updated by voice commands. This could likely be DRYed up too, but this is a demo, after all, not production code.

Notice that this design means there’s very little business logic to add to any given activity to add voice interactions. You don’t have to fiddle with the microphone, explicitly start speech recognition, etc. — that’s all handled by Spokestack, which is managed by the parent VoiceActivity.

There are, however, two details that are particularly important:

- The

Spokestacksetup inVoice, specifically how it deals with wake word and NLU data files

For this tutorial, we’re taking the simple approach of including all our data files in the assets folder (thus distributing them with the app itself) and simply decompressing them to the cache folder on startup. To decrease app size, you can choose to omit these files from the distribution and download them if absent, possibly forcing the app to redownload them based on version changes. It’s important to think up front about how you’ll distribute updates to your NLU model, since it essentially determines which features are available via voice.

- The permission request in

VoiceActivity

Spokestack needs the RECORD_AUDIO permission to use the device’s microphone. It’s automatically included in your manifest when you declare the Spokestack dependency, but starting with Android API level 23, you’ll also need to request it at runtime. Since the user can revoke the permission at any time in their settings, we check for it and re-request every time a VoiceActivity is created.

The way things are set up here, the microphone permission will also be requested on app startup. In a real app, you’ll want to reorganize this to explain the permission before requesting it in order to provide a better user experience.

Recreating the Google Assistant

With our voice integration set up, let’s take a look at how it’s used. Open up DeviceControlActivity and scroll to the bottom.

inner class Listener : SpokestackAdapter() {

override fun nluResult(result: NLUResult) {

if (result.intent == "command.control_device") {

val dataUri = Uri.Builder()

.appendQueryParameter("device", result.slots["device"]?.rawValue)

.appendQueryParameter("command", result.slots["command"]?.rawValue)

.build()

setUiFromIntent(dataUri)

}

}There are several other methods in SpokestackAdapter that we could take advantage of to make our UI more responsive and log errors, but all we’re interested in for the purpose of this demonstration is receiving results from the app’s NLU. What we’re doing here is reusing our deep link processing that’s in place for Google Assistant: when Spokestack’s NLU gives the app an intent that matches the current scene, we use that intent’s slots to construct a URI containing the query parameters we’ve set up for our App Action. The schema and host don’t matter because we’re already in the activity we want to be in. If we wanted to transition somewhere else, we’d have to make a full URI and use the startActivity method; this is what MainActivity does to route button presses to different activities.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, a proper voice experience does require a bit more code than this. You’ll want to handle intents that aren’t meant for the current activity, respond intelligently, and so on. To do all this in a maintainable, understandable way, you want what’s called a dialogue manager component. Watch this blog for more on that in the future!

A couple more notes about DeviceControlActivity:

- Take a look at

onResume. It routes the URI inintent?.datatosetUiFromIntentjust like our NLU event handler above. The presence of a URI indatais how you’ll know if you were reached via voice command, unless you’ve explicitly deep-linked to this activity somewhere else. If that’s the case, you’ll want to include an extra query parameter somewhere to help the app tell the links apart.

We’ve overridden onResume from VoiceActivity here to avoid an awkward scenario where the TTS response starts playing before the system has completed the transition to the new activity, which causes playback to pause when the transition does finish.

populateVoiceMapsdoes a simple synonym mapping of potential slot values (what the user might actually say) to canonical device names — in this case, we’re actually mapping straight to the UI components that represent those devices. This is because Google only lets us specify parameters for custom intents as plain text, rather than allowing the full expressive power of entities that’s available to built-in intents. Hence, we can’t do that normalization inactions.xml. In Spokestack’s format, we can fix this using a selset slot, but since user queries could come from either Google or Spokestack, we’ve left the parsing logic in the app so both query types can be handled the same way.

Time to talk back

Once you’ve mastered the basics of voice navigation we’ve talked about here, you’ll naturally want to start thinking about how your app should respond to users. We’ve given quick examples of this in both DeviceControlActivity and SearchActivity, but let’s talk briefly about the latter.

In SearchActivity’s setUiFromIntent, we extract the “item” slot (the presumed search term) from the data URI and use it in a TTS response to the user. We end the response by asking the user if they want to search again. To make this a seamless experience for the user, we’ve added the following event handler to our Listener inner class:

override fun ttsEvent(event: TTSEvent) {

when (event.type) {

TTSEvent.Type.PLAYBACK_COMPLETE -> spokestack.activate()

else -> {}

}

}This snippet automatically reactivates ASR when Spokestack finishes playing the audio for a TTS prompt, so the user can give another search if they want. If they say nothing, the ASR will deactivate after a timeout.

That brings us to one last point: in its current state, voice integration in the sample app can only be accessed via wake word (“Spokestack”, in this case). It’s easy enough to add a microphone button of your choosing, and it should call spokestack.activate() just as our TTS listener above. If you want to make your button work like a walkie-talkie, you can call spokestack.deactivate() when the user releases it; otherwise, calling deactivate is unnecessary.

Conclusion…or is it?

Congratulations; you have an app that not only makes its features accessible via Google Assistant, but continues that voice interaction via its very own voice layer! We’ve only scratched the surface of making a fully immersive voice experience here, but check out our other tutorials and documentation to learn more.

On that note, if you were frustrated by our final caveat—that we don’t have any UI feedback for our voice interactions—then part 3 of the series is for you. We’ll take what we’ve developed here and drop in Spokestack Tray so that our users can see what they’re saying and interact with Spokestack more naturally.

Originally posted November 30, 2020