Porting the Alexa Minecraft Skill to Android Using Spokestack

This post is part of the Porting a Smart Speaker Voice App to Mobile series, which discusses how to turn an Alexa skill into a mobile app using Spokestack as a replacement for Amazon’s voice services. Other articles in the series can be found at the following links:

- Part 1: Voice Apps on Smart Speakers

- Part 2: Voice Apps on Mobile

- Part 3: Import an Alexa or Dialogflow Interaction Model

- Tutorial: Create an Alexa-Compatible Dialog Manager in Swift

- Tutorial: Porting the Alexa Minecraft Skill to iOS Using Spokestack

- Tutorial: Porting the Alexa Minecraft Skill to Android Using Spokestack (You are here!)

- Tutorial: Porting the Alexa Minecraft Skill to React Native Using Spokestack (Coming Soon)

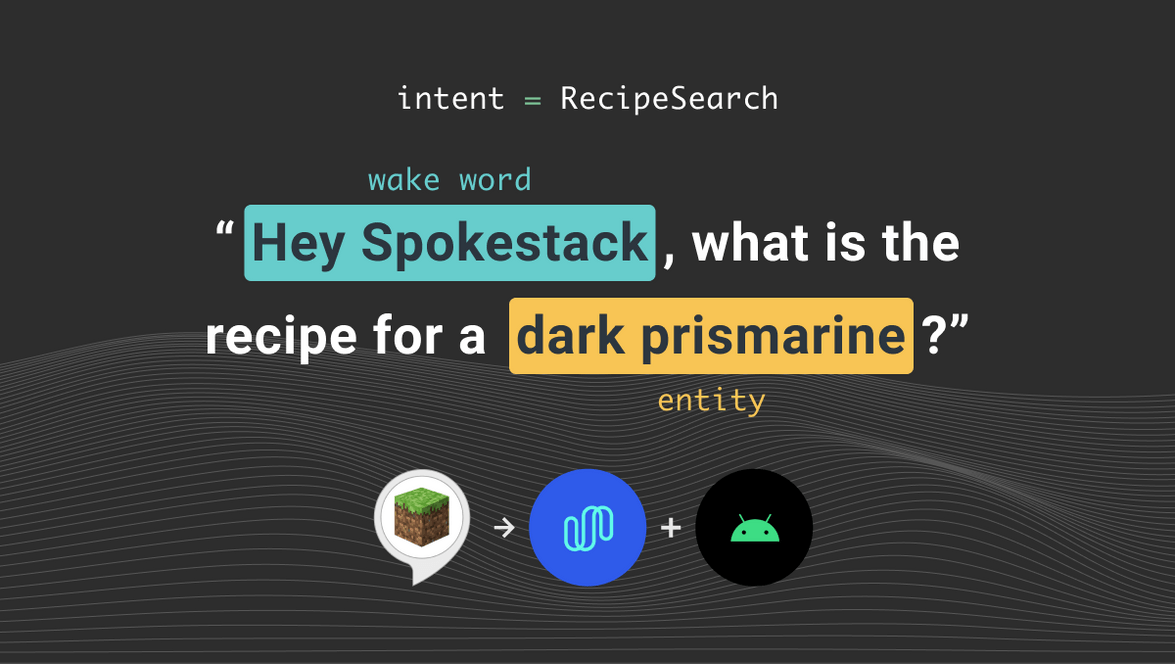

This tutorial will walk you through the details of porting an Alexa skill to Android. To be specific, we’ll be recreating a skill that lets the user ask for a recipe in Minecraft. The full code for our finished app is here; feel free to download it for reference as you follow along. We’ll go through it step by step in the tutorial for sake of discussion.

First, a quick note on language choice. Android development has been moving toward Kotlin as its preferred language. Our other Android guides are written with that in mind, but we’re going to switch gears for this one. Amazon provides a Java SDK for Alexa development, so in order to ease friction between the two ecosystems, we’ll port the skill to Java instead of Kotlin. The example code here shouldn’t be too complex to translate into Kotlin if you’re familiar with it.

With that pretext out of the way, let’s get to coding. Our first job will be to establish the mobile-specific stuff you don’t have to do when setting up an Alexa skill.

App Scaffolding

On Android, the Activity is one of the fundamental building blocks of an app. Roughly speaking, an Activity is the code for a single scene’s behavior (minus a description of the visual layout, which is done elsewhere). If you’re using Android Studio — and you probably should be for this — you’ll want to open a new project and use the “Empty Activity” template. This will create all the boilerplate we’ll need, along with a MainActivity we’ll be referring to throughout the rest of this guide. When you’re setting up a new project, Android Studio also asks for a minimum SDK. We chose 21 for this guide.

To avoid cluttering this guide too much, we’ll omit the full build.gradle files and the detailed code for requesting microphone permissions in MainActivity. See the example files for copy/paste-able examples. Here are the important things you’re looking for in app/build.gradle:

- The

native-dependenciesplugin application and the block associated with it that retrieves Spokestack’s native library (at the top of the file) - The

ndkVersionline in theandroidblock. See here for information on installing the NDK, and make sure your version number inbuild.gradlematches the one you install. - The

compileOptionsblock, also underandroid. These options allow some of our dependencies to build properly. - The Spokestack library dependency and others associated with it (at the bottom of the file)

And in the build.gradle in your root directory:

- A

classpathdependency that retrieves thenative-dependenciesplugin

OK, time to dive into MainActivity and set up Spokestack to handle user speech.

Can you hear me now?

In order to turn your phone into a (better) smart speaker, you need to take control of the microphone and process user input from it. That’s why we requested the permissions in the previous section. The Spokestack component used to actually do something with that data is called SpeechPipeline. It handles collecting audio from the user and turning it into text (automatic speech recognition, or ASR), and there are other components for extracting meaning from that text and for generating audio in response to the user. These exist separately in the Spokestack library so that an app can pick and choose which ones it needs. We need them all for this app, so let’s make a class to contain and control them all. Let’s call it … I don’t know … Spokestack.

Since we’re building all three components there, this is another file we won’t discuss in its entirety; you can find the full version in the demo project. For the purpose of this guide, we’re just going to pretend it exists and talk about how to interact with it in MainActivity.

public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

private Spokestack spokestack;

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

this.viewBinding = ActivityMainBinding.inflate(getLayoutInflater());

setContentView(viewBinding.getRoot());

// see if we were granted the microphone permission

// during a previous session; if so, go ahead and build

// Spokestack components

if (checkMicPermission()) {

buildSpokestack();

}

}

// other code...

private void buildSpokestack() {

// extract the models from the asset bundle if we need to

checkForModels();

this.spokestack = new Spokestack(getApplicationContext(), this);

try {

// start the speech pipeline

this.spokestack.start();

this.spokestack.launch();

} catch (Exception e) {

Log.e(logTag, "Problem starting Spokestack", e);

}

}

}This is all we need to interact with the components we’ve built — the start method gives Spokestack control of the microphone via its SpeechPipeline so that we can start hearing the user. If you look at how we’ve set the pipeline up for this project, though (in Spokestack), you’ll notice a line that sets the pipeline’s “profile” to PushToTalkAndroidASR. This means that we’re not using a wake word (e.g., “Alexa”) to tell the app to start actively listening to the user. Spokestack does support this, and you can see an example configuration in our Android cookbook, but we’re going to use a button here for sake of simplicity. That means we’ll need a microphone button and a handler that starts sending audio through speech recognition when the button is tapped:

// still in MainActivity

void activateAsrTapped(View view) {

this.spokestack.activateAsr();

}That wasn’t so bad, was it? We’re manually activating the ASR, but the configuration we’ve set up in the Spokestack class will handle deactivating it after speech stops.

Note: We’re using the Android ASR here because it’s the easiest way to demo ASR, but it’s not available on all devices. See our ASR documentation for more information on it and the other ASR providers Spokestack integrates with.

Also note that the Android emulator cannot record audio. You’ll need to test ASR on a real device.

With those caveats behind us, our next job is to make an effort to actually understand the user…

Integrating NLU

Part 3 of this series includes a refresher on the concept of natural language understanding (NLU) as well as instructions for converting your Alexa model into a format usable by Spokestack, so we’ll just cover the Android-specific parts here.

The configuration for the Spokestack NLU is in the Spokestack file, just like our ASR setup. It requires three external files — a TensorFlow Lite model, a JSON metadata file that describes its output, and a vocabulary file used to transform ASR results into input for the model. These files aren’t huge (typically < 20 MB total), but they’re big enough that you probably want to distribute them compressed to keep your app download size down.

To do that, place all three files in the src/main/assets directory under your app’s root directory. You may have to manually create assets, but the others should have been created along with your project. Files in the assets directory have to be decompressed at runtime to be used. We typically do that by decompressing them to the application’s cache directory on startup, then on subsequent starts checking if the files exist and decompressing again if the user has cleared the cache or the app has been updated to a new version. This is the checkForModels() method from the previous section. In the demo app, this code is in MainActivity, but you could put it elsewhere for sake of cleanliness:

private void checkForModels() {

// PREF_NAME and VERSION_KEY are static Strings set at the top of the file;

// we want PREF_NAME to uniquely refer to our app, and VERSION_KEY to be

// unique within the app itself

if (!modelsCached()) {

decompressModels();

} else {

int currentVersionCode = BuildConfig.VERSION_CODE;

SharedPreferences prefs = getSharedPreferences(PREF_NAME, Context.MODE_PRIVATE);

int savedVersionCode = prefs.getInt(VERSION_KEY, NONEXISTENT);

if (currentVersionCode != savedVersionCode) {

decompressModels();

// Update the shared preferences with the current version code

prefs.edit().putInt(VERSION_KEY, currentVersionCode).apply();

}

}

}

private boolean modelsCached() {

String nluName = "nlu.tflite";

File nluFile = new File(getCacheDir() + "/" + nluName);

return nluFile.exists();

}

private void decompressModels() {

try {

cacheAsset("nlu.tflite");

cacheAsset("metadata.json");

cacheAsset("vocab.txt");

cacheAsset("minecraft-recipe.json");

} catch (IOException e) {

Log.e(logTag, "Unable to cache NLU data", e);

}

}

private void cacheAsset(String assetName) throws IOException {

File assetFile = new File(getCacheDir() + "/" + assetName);

InputStream inputStream = getAssets().open(assetName);

int size = inputStream.available();

byte[] buffer = new byte[size];

inputStream.read(buffer);

inputStream.close();

FileOutputStream fos = new FileOutputStream(assetFile);

fos.write(buffer);

fos.close();

}The configuration in our Spokestack class expects the files to be located in the cache directory (and named as listed above). If you change the files’ locations, you’ll need to update the file paths in Spokestack.java as well.

Other than that, though, you’re all set with NLU. Doing the actual utterance classification happens each time an ASR transcript is available, via the following code in Spokestack. Note that it’s an overridden method; Spokestack implements the Spokestack library’s OnSpeechEventListener interface to receive events from the SpeechPipeline.

@Override

public void onEvent(SpeechContext.Event event, SpeechContext context) throws Exception {

switch (event) {

// other events

case RECOGNIZE:

// the RECOGNIZE event signifies that a result is available from the selected ASR.

String utterance = context.getTranscript();

NLUResult result = this.nlu.classify(utterance).get();

Response response = this.dialogManager.handleIntent(result);

speak(response);

break;

}

}Notice what comes after the NLU does its thing. That’s our next step: putting another small piece of Amazon’s backend right in the app.

Recreating Dialog Management

A dialog manager takes the intent and slots from the NLU along with the current context (or “state”) of the conversation and decides what sort of response the system should give. In the Alexa SDK, this means that the system consults, in order, a series of RequestHandlers that have been registered to a SkillStreamHandler.

In Java terms, this means you have a series of classes that all implement an interface for handling user intents, and a manager class somewhere that has an ordered list of these handlers. When a request comes in, the first handler capable of responding to the request is chosen. That’s all easy enough to replicate without the help of Lambda or the SDK, so let’s do it.

First, the handler interface. We’ll stick closely to the names from the Alexa SDK for sake of analogy even though our objects will be slightly different.

public interface RequestHandler {

public boolean canHandle(HandlerInput handlerInput);

public Response handle(HandlerInput handlerInput);

}We’re not returning an Optional from handle like Amazon does just to maintain compatibility with a wider range of Android devices (it wasn’t introduced until API 24).

And now the manager itself. It’s not much to look at either.

public class DialogManager {

private List<? extends RequestHandler> requestHandlers;

private Session session;

public DialogManager(List<? extends RequestHandler> handlers,

Cookbook cookbook) {

super();

this.session = new Session(cookbook);

this.requestHandlers = new ArrayList<>(handlers);

}

public Response handleIntent(NLUResult nluResult) {

HandlerInput handlerInput = new HandlerInput(nluResult, this.session);

Response response = null;

for (RequestHandler handler : this.requestHandlers) {

if (handler.canHandle(handlerInput)) {

response = handler.handle(handlerInput);

break;

}

}

updateSession(nluResult, response);

return response;

}

}The main addition here is the Cookbook, which we use to look up Minecraft recipes. It’s related to the conversation state, so we’re putting it right in the Session, but if we had a more complex response generation system, it would probably belong there instead. In the Amazon SDK, the Session object is nested inside a RequestEnvelope, but we don’t have a need for most of the other things their SDK exposes via objects like RequestEnvelope and AttributesManager, so we’ve flattened out the API.

That’s it for the guts of the dialog management system. Setup is done, once again, in the Spokestack class:

private void buildDialogManager() {

String cacheDir = this.appContext.getCacheDir().getAbsolutePath();

List<? extends RequestHandler> handlers = Arrays.asList(

new LaunchHandler(),

new RecipeHandler(cacheDir),

new HelpHandler(),

new RepeatHandler(),

new ExitHandler(),

new ErrorHandler()

);

this.dialogManager = new DialogManager(handlers);

}You can tell what most of those handlers do from their names; their rather simple code is available in the demo project. Remember that this is a Minecraft skill whose main job is to look up “recipes” for different in-game items. Hence, most of the interesting work is done in RecipeHandler. A discussion of its business logic is outside the scope of this tutorial, but do take a look through the source code. It’s heavily commented to offer some tips for voice search, an important consideration for many apps.

We’ve now dealt with the input side of the equation, so all that’s left is to make the app talk back. It’s not an easy task, but Spokestack makes the implementation simple.

Speaking our mind

Before the app speaks, we have to figure out what it should say. This example skill has a simple call-and-response-style conversation, so there aren’t many different states the conversation can be in. An app designed to carry on a longer conversation will probably want a different structure, but we can get away with putting our prompts in a simple enum and selecting from it based on intent at runtime:

public enum Responses {

WELCOME("Welcome to %s. You can ask a question like, what's the recipe for a %s? ... Now, what can I help you with?"),

ERROR("Sorry, I can't understand the command. Please say it again."),

// other responses...

private String prompt;

Responses(String prompt) {

this.prompt = prompt;

}

public String formatPrompt(String ... params) {

return String.format(this.prompt, params);

}

}Notice that the responses are templates, allowing us to inject data at runtime. Again, we’re taking advantage of our app’s simplicity; you might want a more robust templating solution than plain String.format() for yours. We’ve also gotten rid of Alexa-style reprompts, which is the name for an additional prompt that can be delivered if the app asks a question but doesn’t receive an answer for a pre-set amount of time. There’s nothing stopping you from implementing reprompts in Spokestack; it’s just once again outside the scope of this guide. We have a separate tutorial with more information if you’re interested in including reprompts.

The Responses enum covers looking up and formatting our responses; all that’s left is to turn them into audio and play them to the user. Unfortunately, dealing with media players on mobile platforms isn’t very straightforward. If your app already deals with audio playback, you may wish to approach TTS differently, but Spokestack can handle both generation and playback. This is how the TTS component is set up in our trusty Spokestack class:

private void buildTTS() throws Exception {

if (this.tts == null) {

this.tts = new TTSManager.Builder()

.setTTSServiceClass("io.spokestack.spokestack.tts.SpokestackTTSService")

.setOutputClass("io.spokestack.spokestack.tts.SpokestackTTSOutput")

.setProperty("spokestack-id", "YOUR-ID-HERE")

.setProperty("spokestack-secret", "YOUR-SECRET-HERE")

.addTTSListener(this)

.setAndroidContext(this.appContext)

.build();

}

}It’s the SpokestackTTSOutput class that’s responsible for playback; if you want to manage that yourself, you’ll want to configure a TTSListener to receive and play the audio URLs that are returned by the TTS service. Here, Spokestack is set up as a listener, but it only recognizes error events so they can be logged appropriately.

Note also the spokestack-id and spokestack-secret configuration properties: these credentials are available from the account section of the Spokestack website.

With the TTS component established, generating audio is as simple as turning our prompt text into a SynthesisRequest and sending it along:

private void speak(String text) {

SynthesisRequest request = new SynthesisRequest.Builder(text).build();

this.tts.synthesize(request);

}Each request handler pulls back a prompt template from the Responses enum and calls formatPrompt on it to fill it with dynamic data, so by the time the prompt is in a Response object, it’s already in its final form, and all we need to do is pull it out and send it through TTS.

Some of the prompts end in questions, which imply that the microphone should be left open (and ASR activated) after the prompt plays. This is done in Spokestack by listening for the PLAYBACK_COMPLETE event from the TTS component and calling pipeline.activate() if the last response in the Session indicates expected user input.

You’re done!

With ASR, NLU, and TTS in place, you’ve effectively recreated the Alexa experience…without Alexa! On a mobile device, you’ll have much more freedom to make your touch-based UI match your voice experience, and of course you can manage user accounts your way instead of Amazon’s.

This tutorial has been a little involved, and we know we haven’t gone over every aspect of the experience with a fine-tooth comb, so if you run into any issues, don’t hesitate to reach out!

Originally posted June 09, 2020